Does “The Bigger the Better” Apply to Lizards?

Fun Fact: Some lizards can clone themselves!

Take the Colorado Checkered Whiptail, Aspidoscelis neotesselatus for example.

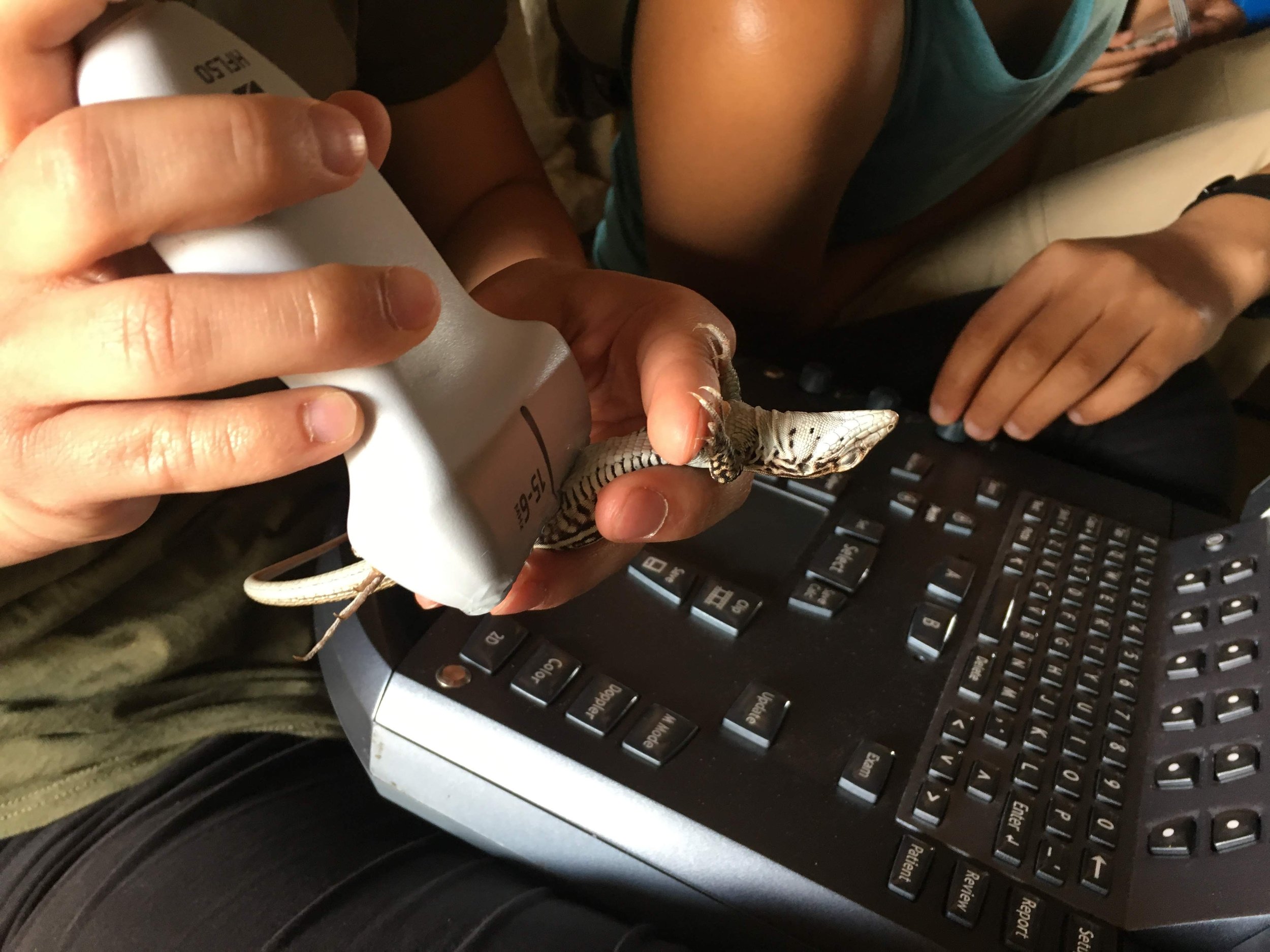

A Colorado Checkered Whiptail is collected and assessed by a member of Caracalas’ research team (2019).

Parthenogenesis is the development of an embryo from an unfertilized egg. Some species of plants and animals are able to reproduce this way, saving valuable energy that would otherwise be used for costly reproductive behaviors such as courtship and parental care. All Colorado Checkered Whiptails are female!

NCHS board member Hannah Caracalas and a team of researchers from Colorado State University, Utah State University, the National Wildlife Research Center in Florida, and the Erell Institute, investigated how the size of a checkered whiptail impacts its ability to have larger clutches, larger follicles, and larger eggs. (Note that the researchers use the word “follicles” to refer to eggs throughout the earlier developmental stages. A “clutch” is a group of follicles or eggs.) They further examined the physiological effects of doing so, and what this may mean for the survival of the species.

Caracalas and a Colorado Checkered Whiptail (2019).

Theoretically, a mother can’t simultaneously increase both the size of her offspring and the number of offspring produced. So what are the trade-offs of producing larger clutches or larger eggs?

Caracalas’ team collected and assessed checkered whiptails in El Paso County during two reproductive seasons in 2018 and 2019, during which time they:

Measured the size of the lizard

Toe clipped new captures for long term marking (a traditional marking method in field research for reptiles. The longest rear toe was not clipped, given that it is fundamental for running.)

Marked the lizard with a non-toxic paint pen

Took a blood sample (to assess physiological parameters)

Administered an ultrasound to assess:

Gravidity (how far along the lizard is in “pregnancy”)

Clutch size

Follicular/egg size

The lizards were then released back to their original locations.

How did the size of the lizard affect the clutch/follicle sizes?

Caracalas’ team found that larger females that laid clutches of two follicles had a larger overall follicle size, when compared to those that laid clutches of one or three. This is the effect of body size on clutch/follicle size trade-off.

The fact that eggs in clutches of two were larger than clutches of one or three suggests that a clutch of two is the optimum level of energy investment for this species. Clutches of two were, unsurprisingly, the most frequent clutch size found during this study.

It makes sense that the most commonly found clutch size (two) was the most energy-efficient. There is a trade-off between clutch and follicle size, and a clutch of two seems to be the largest possible clutch without the cost of follicle quality and size. This is the clutch size and follicle size trade-off.

So what’s the catch?

The blood samples showed elevated levels of oxidative stress (reactive oxygen metabolites or ‘ROMs’) in females who laid larger clutches (two or three follicles) and larger follicles, when compared to females who produced a single clutch with one small follicle.

This means that investing in larger clutches and follicle sizes comes at a cost: possible oxidative damage. These lizards can only make so many large clutches/follicles before it has a negative impact on their own health.

“If for example, elevations on oxidative stress markers such as reactive oxygen metabolites lead to tissue damage, then elevated physiological stress could result in decreased survival within populations.”

Caracalas expounds on ROMs:

“ROMs or reactive oxygen metabolites (also called free radicals or reactive oxygen species) are things that are produced in the body during metabolism and have their roles in various cell processes. They are usually kept in balance by antioxidants, and so if that becomes imbalanced and the ROMs start damaging the cells-- that is what causes oxidative stress.

That imbalance can be caused by all kinds of things, environmental stress (like UV or heat exposure), pollution, in humans it can be smoking or drinking, certain medications, too much sugar, you get the idea. So our line of thinking was that reproduction is a stressful activity, stress increases ROMs potentially past the point of where they can be kept in check, and oxidative stress happens.

So we hypothesized that females who are putting more energy/effort into reproduction, producing larger eggs or larger clutches, would have higher levels of oxidative stress. And we did find that!”

This is the effect of physiological state on clutch/follicle size trade‑off.

Colorado Checkered Whiptail is marked with non-toxic paint during field exam (2019).

What are the advantages of being a large lizard?

“Larger females tend to have access to greater resources, and thus are more likely to allocate energy towards reproduction, resulting in larger clutches and/or larger follicles.

Our findings suggest that larger A. neotesselatus females able to invest in larger clutches were also able to produce larger follicles, without having to compromise, suggesting that access to resources and female size are key in determining female reproductive success.”

Caracalas et al, 2020

Individual reproduction collectively determines population survival.

A Colorado Checkered Whiptail is released back into its original location after field assessment, marked with non-toxic paint (2019).

Why is this important?

Caracalas’ research brings us closer to understanding what traits best benefit whiptails in maintaining their numbers, moving us a step closer to how we can best support them in the long term.

Many thanks to the team who contributed to this publication, and we look forward to seeing developments in this area of research!

Contributors to this research:

Hannah E. Caracalas, S. S. French, S. B. Hudson, B. M. Kluever, A. C. Webb, D. Eifer, A. J. Lehmicke, and L. M. Aubry.